November 2019 in Wuhan

- Becky

- Jan 2, 2022

- 8 min read

Back in November 2019, I didn’t know that my visit to Wuhan, China was perfectly coincident with the launch of the covid-19 epidemic. No one did, unless you believe that the virus was engineered in a lab, right there in Wuhan. Personally, I’m inclined towards the bat theory. I didn’t eat any bats while I was there. Or if I did, they were healthy bats. Who knows what was really in those plates of food.

Since May that year I’d been competing for a juicy promotion at work. A high-priced consultant flew in from New York for an afternoon, for my second round of the interview process, after I’d aced the first round. And then she flew straight home. She told me I was a strong candidate, definitely in contention, in stark contrast to the internal candidates she usually interviewed, pro forma only, video conference only. My peers seemed to think I was a shoo-in. Instead I was a boot-out. But that would be a year later.

My boss was a salesy-type, friendly on the surface, hard to read what was underneath. He’d encouraged me to compete for the promotion, and promised to coach me. I’d call him glad-handed—a term to describe a person who smiles and shakes your hand and tells you you’re great—but instead of handshakes, he did fist bumps. Back then, pre-covid, fist bumps were mostly confined to the Black community, quite rare in white middle-aged men like my boss. He was known and good-naturedly mimicked for that cultural-appropriation oddity. So instead of being glad-handed, I'm going to say he was a glad-fisted.

Feel free to use that term when apt.

My new boss, an external hire from a Much Larger Company, had started work the month before, in October, 2019. I tried to convince her to go on the China trip instead of me, thought it would be good for her to get to know the China team in person. But she insisted that I go. So did the head of the China office. He liked me and had wanted me to get the promotion; we worked well together, mutually respectful of the other’s areas of expertise. He said, We all want you to come to China for the seminar. I was still unsure, a bit tender from the not-promotion.

The final straw that broke the back of the camel of my reluctance was an offer from Zhyun, the person who reported to me directly in China. She said, We can take the train together from Shanghai to Wuhan and back instead of flying.

She knew how to convince me. I’m a sucker for trains. Especially when I’d get to travel during the day, across new-to-me parts of China. I agreed.

Our company, MNC, put together and hosted a seminar once a year, in which customers would speak about problems they’d addressed using MNC equipment. We used to host seminars in multiple regions worldwide, but had narrowed our focus to China, a region that was spending a lot of money in high-end semiconductor equipment in accordance with the China 2025 initiative announced by Xi Jinping. Ours were popular seminars, attended by two to three hundred people at each venue. This year we were taking the seminar to Wuhan for the first time; the previous year we’d been in Shanghai and Beijing (where I'd toured the Forbidden City with Zhyun). There was a new facility in Wuhan that made computer memory chips. Wuhan was eager for knowledge.

My group was responsible for the whole darn thing. Not only the logistics but also assembling the program, figuring out the topics, and inviting-slash-cajoling-slash-pleading-slash-bribing (within the law) speakers to fly in from around the globe to share their knowledge.

There was a web-based training course required each year at MNC that taught us customer-facing employees about what kinds of bribes were legal in which countries. These legal bribes were called gifts. We also learned what kinds crossed the line into murky territory, and what kinds ought to be avoided unless you're ninety-seven percent sure you can get away with it. I don’t recall the exact title of the course, but it was something like, Don’t Get MNC in Trouble And You’ll Personally Go to Jail, Too.

I let the China team handle the speaker gifts. But my team handled everything else.

I’m not sure why my new boss didn’t want to go, and I don’t mean to imply she had some agreement with the bat. Seems unlikely she’d try to get rid of me in a dramatic way like that, when she could just lay me off a year later, after she had her feet under her.

So I got on a plane in San Francisco the day before my birthday, and landed in Shanghai at ten pee-em on my birthday. All but two hours of my birthday had been lost due to that rascal, the International Date Line. I didn’t really think missing my birthday would matter to me much. And then I got to my hotel and opened my suitcase. On top were two birthday cards, one from my brother Jon and the other from my State Farm agent. The two people who can be relied upon to send me a birthday card on time, every single year.

I don't really care all that much about cards. Usually don't send them myself. But I'd tucked them into my suitcase, figuring it would be fun to have cards to open, here in Wuhan, halfway around the world from home.

I opened the State Farm one first. Happy birthday, it said. The signature was in the office manager's handwriting and read, Bob and Staff. That's what it said every year, Bob and Staff. It was a rite of passage when my kids were old enough to have car insurance and get birthday cards from Bob and Staff.

Then I opened Jon's. Jon used to send bland, generic birthday cards with Love, Jon scrawled at the bottom. My sister Renie and I would joke, Did you get your Love, Jon birthday card this year? But since our parents died, he’d been making more and more of an effort. This year he’d selected a card with a heartfelt sentiment and written a few personal sentences about how much he enjoyed our newfound connection, since I’d started calling him every Friday during my commute home from work.

I was taken by surprise at how much his card choked me up, and also by the tiny touch of resentment I felt, having missed my birthday that year except for Jon’s card. And Bob's. Ah well. Be a big girl, I told myself. There’d be a birthday toast during Thanksgiving with my family, later in the month. Good enough, right? It wasn’t a five or a zero year. I rolled my eyes at myself. Sheesh woman, I thought. It doesn’t really matter.

The next morning I met Zhyun in the bigger of the two Shanghai train stations, and we boarded for the several-hour trip to Wuhan. Zhyun was a terrific travel companion, fluent in English after having spent years in the UK working on her doctorate in physics.

She’d grown up in Beijing, the second daughter of two professors, highly placed in the Party. Her parents were allowed two children during the one-child proclamation because Zhyun’s older sister was considered disabled. A second child was therefore allowed, conceived and raised for the purpose of taking care of her sister, as Zhyun explained.

Turns out her sister was very mildly disabled, and had grown up to become prominent psychologist in Beijing. So Zhyun has been able to live her own life, including getting a PhD overseas and taking a job in Shanghai. She remains a caretaker through to her bone marrow, though. I call her my Chinese daughter, because she would pick me up in a taxi every day and ride with me to the office in Shanghai. She would ask if I was comfortable, needed anything. She’d also take my elbow when I crossed a busy street. That would have amused me more if I hadn’t been so woozy from jet lag that I might have gotten hit by a car without her.

Zhyun and I got on the train to Wuhan and settled in. I spent the hours looking out the window at the gray landscape zipping by: farmland, hills, and mountains once we were farther inland. Small cities with huge blocks of identical high-rise apartments. Coal plants in the outskirts of each city.

Zhyun said, I wouldn’t live in an apartment built after 1960. You can’t trust the construction. She lived in an older building on the outskirts of Shanghai.

Through my earbuds, Scarlatti’s Le Violette was playing. The sheet music was open on my lap. It’s hard to memorize a song in a language you don’t know, especially when you’ve just accomplished yet another in a long line of birthdays.

We arrived in the Wuhan train station late in the afternoon, and took a taxi to our hotel. It was a short taxi ride, and I took in as much of the city as I could: moderate size, nondescript, murky air. We arrived at a fancy conference hotel, attached to a large convention center.

The rest of the higher-ups from the China team were already there; they’d flown from Shanghai, long past the romance of seeing the landscape of the interior of their country. We greeted one another warmly, with hugs or handshakes. No fist bumps.

I checked into a luxurious hotel room with a balcony overlooking a lake. Washed my face, brushed my hair, unpacked and then FaceTime'd my cousin in Maryland, returning her call from the day before, the missing day of my birthday.

You’d never guess where I am—Wuhan! I said to her.

Where’s that? she replied.

Very soon the world would recognize Wuhan.

Half an hour later, I met Zhyun in the lobby to see about dinner. She said, Let’s just go to one of the restaurants in the convention center.

We walked about a mile through the higantic convention center, no exaggeration. I stopped to take a photo of a booth marked in English, Cash Recycling System. What could that be? A money laundering machine, where you put your dirty old cash in, and you get rejuvenated cash out, minus a handling fee? Or maybe you just insert the cash you no longer want, like empty soda cans and junk mail. Bye-bye, unwanted cash.

This is what I love about traveling, the funny ordinary things you see. Recently I showed my sister a box of Sudafed that I’d bought during a business trip to Belgium. The box had embossed Braille on it, presumably reading pseudoephedrine. How great is that?

I’ve used up all the Sudafed and have refilled it several times with American generic Sudafed. The box is battered and has lost its crisp ninety-degree angles. The end flaps don’t really close any longer. But the Braille is just so great.

Zhyun and I stopped for a few minutes at the room where our seminar would be held the next day. Looked good: theater-style, nice raised podium up front, large, high-quality screen. MNC-branded pens and tablets already at each place in the audience. Ready to go, thanks to Zhyun’s hard work.

We strolled onwards, and finally arrived at the restaurant where we were meeting for dinner. I opened the door, and my friends from the Shanghai team shouted, Surprise!

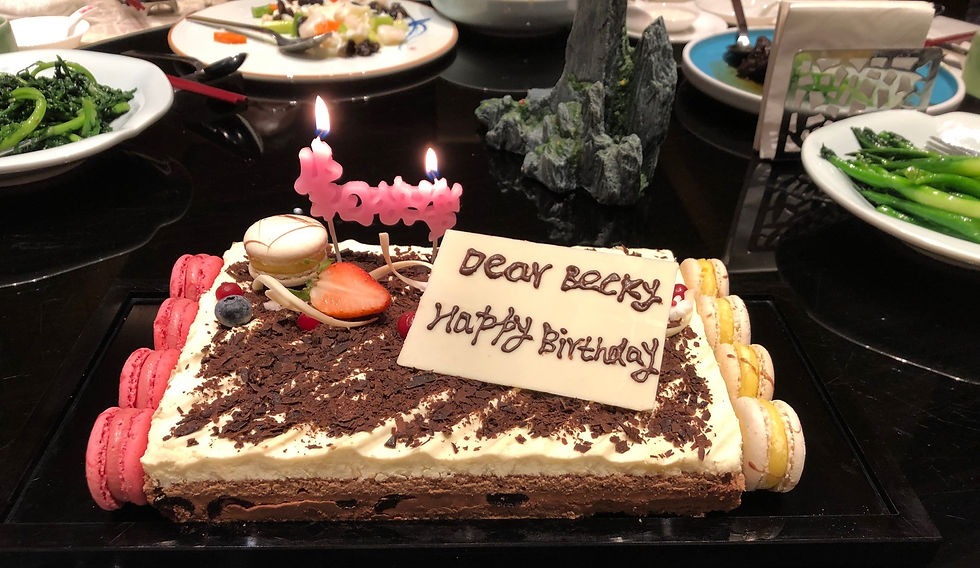

They’d arranged a birthday banquet for me, complete with funny little gifts and a western-style birthday cake.

Wuhan in November, 2019. A place that would soon become famous for the beginnings of a worldwide pandemic.

But for me, a time and place where friends and colleagues from halfway around the world cared about me, and wanted me to feel better about missing my birthday.

[Wuhan images and video. That's Zhyun making the bunny ears behind me. Photo creds: Mostly me, with an assist from the waitstaff.]

Comments